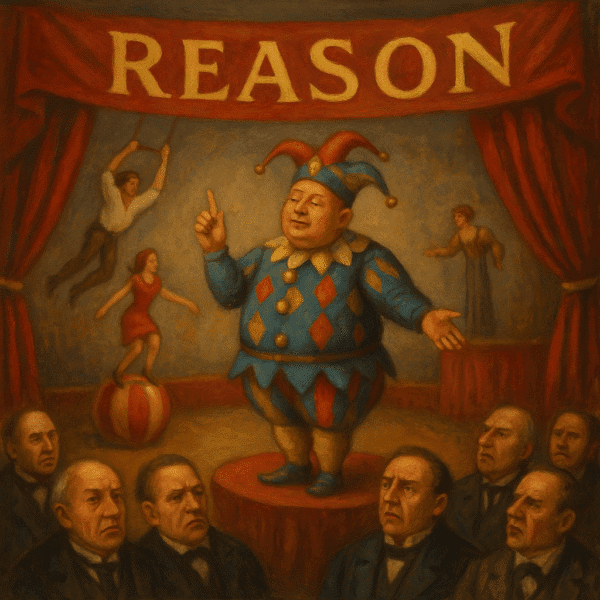

The Enlightenment Circus: Popular Superstition Dressed Up as Reason

Abstract

The Enlightenment is often celebrated as the triumph of reason over superstition. Yet, a closer philosophical and historical analysis reveals a paradox: the Enlightenment replaced one form of faith with another. In elevating “Reason” to an absolute ideal, it reproduced the same structures of dogma, ritual, and moral absolutism that it sought to overthrow. This paper argues that the Enlightenment was less a scientific revolution of thought and more a cultural rebranding of belief—a popular superstition dressed in the costume of rationality. Drawing from critical theorists, historians of science, and modern sociology, the paper explores how this intellectual shift led to bureaucratic modernity and the secular priesthood of management.

Introduction

The Enlightenment (circa 1650–1800) is typically portrayed as humanity’s coming of age, when rationality displaced religious dogma and superstition. This triumphal narrative persists in education, policy, and cultural mythology. However, the claim that Enlightenment rationality represented a clean epistemic break from theology is contestable. As Adorno and Horkheimer (1947/2002) observed in Dialectic of Enlightenment, the movement’s rationalism often concealed new forms of domination and myth-making. Rather than abolishing superstition, the Enlightenment transformed it into a new religion of reason—its clergy being philosophers, and its rituals being scientific progress, universal rights, and economic expansion.

Historical Background

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the philosophical salons of Europe replaced ecclesiastical councils as the center of intellectual authority. Figures such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot positioned themselves as liberators from clerical tyranny. Yet, as Israel (2011) notes, their movement functioned as a “cult of reason” that substituted the metaphysical dogmas of Christianity with the moral absolutism of “rational man.”

While these philosophers invoked Newtonian physics as the model of clarity and truth, most lacked the mathematical or mechanical competence to understand Newton’s work (Cohen, 1999). The Principia Mathematica became a symbol of authority rather than a method of inquiry. In effect, the Enlightenment popularized the imagery of science while divorcing it from its empirical discipline.

Mechanism without Mechanics

The Enlightenment’s central metaphor was the “mechanical universe.” Yet, as Shapin (1996) shows, the philosophers who preached mechanism often misunderstood mechanics. The Newtonian revolution required mathematics, measurement, and experiment; the Enlightenment’s public intellectuals preferred rhetoric and speculation. Consequently, “Reason” became a moral aesthetic—a marker of refinement and civility—rather than a methodological commitment.

This gap between rhetoric and rigor produced what this paper calls mechanism without mechanics: a worldview that invokes scientific authority while operating without empirical accountability. The phenomenon persists today in corporate, political, and academic institutions that weaponize “data” and “innovation” as symbols of virtue.

The Myth of Reason and the Rise of Bureaucratic Faith

Max Weber (1919/2004) identified modern bureaucracy as the institutional child of Enlightenment rationality: a system of impersonal rules that promised fairness but produced disenchantment. The rationalization of life became itself a new superstition—faith in procedures as a guarantee of truth.

Adorno and Horkheimer (1947/2002) argued that Enlightenment rationality, untethered from ontology and ethics, turned into instrumental reason: the logic of control, calculation, and efficiency. Under this logic, humans became data points, and knowledge became capital. Rationality, once the servant of wisdom, became an idol demanding obedience.

From Enlightenment to Managerial Priesthood

The modern corporation and university are heirs to the Enlightenment’s secular church. Human Resources departments enforce moral orthodoxy; managers act as priests of organizational salvation, promising redemption through compliance and “culture.” As Boltanski and Chiapello (2005) argue, capitalism absorbed the Enlightenment’s moral vocabulary—autonomy, creativity, progress—turning it into tools of governance.

Like the clergy of old, managerial elites sustain their legitimacy through performance, not ontology. Their sermons are TED Talks; their sacraments are performance reviews. The Enlightenment’s dream of liberation culminated in the bureaucratic management of souls.

Conclusion

The Enlightenment’s failure was not intellectual error but moral hubris. By enthroning “Reason” as an infallible god, it reproduced the superstition it sought to destroy. It preached mechanism without mechanics, freedom without telos, and rationality without wisdom. To recover truth from its ruins, humanity must reunite epistemology with ontology—knowledge with being. Only then can reason cease to be a superstition and become again a path toward understanding.

References

Adorno, T. W., & Horkheimer, M. (2002). Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical fragments (E. Jephcott, Trans.). Stanford University Press. (Original work published 1947)

Boltanski, L., & Chiapello, È. (2005). The new spirit of capitalism (G. Elliott, Trans.). Verso.

Cohen, I. B. (1999). Revolution in science. Harvard University Press.

Israel, J. (2011). A revolution of the mind: Radical Enlightenment and the intellectual origins of modern democracy. Princeton University Press.

Shapin, S. (1996). The scientific revolution. University of Chicago Press.

Weber, M. (2004). The vocation lectures (D. Owen & T. Strong, Eds.). Hackett. (Original work published 1919)