Thomas Aquinas and Aristotelian Eudaimonia: A Christian Synthesis of Human Flourishing

Introduction

The concept of eudaimonia, often translated as “happiness” or “flourishing,” lies at the heart of Aristotle’s ethical philosophy. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle posits that eudaimonia is the ultimate end of human life, achieved through a life of virtue and rational activity. Centuries later, Thomas Aquinas, a towering figure in medieval theology and philosophy, engaged deeply with Aristotle’s ideas, seeking to harmonize them with Christian doctrine. This article explores how Aquinas reframed Aristotelian eudaimonia within a Christian framework, transforming the concept into beatitudo—perfect happiness found in union with God. Through this synthesis, Aquinas not only preserved Aristotle’s ethical insights but also elevated them to align with the Christian vision of human destiny.

Aristotle’s Eudaimonia: The Foundation

Aristotle’s eudaimonia is the telos, or ultimate purpose, of human life. In Nicomachean Ethics (Book I), he defines it as “an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue, and if there are several virtues, in accordance with the best and most complete” (I.7, 1098a16-18). For Aristotle, this flourishing is achieved through the cultivation of moral virtues (e.g., courage, justice, temperance) and intellectual virtues, particularly practical wisdom (phronesis) and contemplation (theoria). The contemplative life, Aristotle argues in Book X, represents the pinnacle of eudaimonia, as it engages the rational faculty most fully, aligning humans with their highest potential.Aristotle’s framework is naturalistic, grounded in human reason and observable experience. Eudaimonia is attainable within the confines of earthly life, contingent on the consistent practice of virtue and the conditions of a well-ordered society. However, Aristotle’s philosophy lacks a supernatural dimension, leaving open the question of whether ultimate happiness can transcend temporal existence.

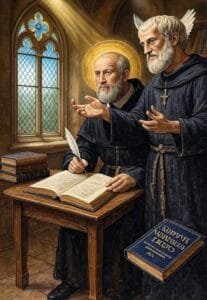

Aquinas’s Engagement with Aristotle

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a Dominican friar and Doctor of the Church, encountered Aristotle’s works through Latin translations and commentaries, which were rediscovered in the medieval West. As a Christian theologian, Aquinas sought to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy with Christian revelation, a project most fully realized in his Summa Theologica and Commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Central to this synthesis was his adaptation of eudaimonia, which he reframed as beatitudo—perfect happiness or blessedness.Aquinas accepted Aristotle’s teleological view that all human actions aim at some good, with happiness as the ultimate end (Summa Theologica, I-II, Q. 1, A. 1). However, he diverged from Aristotle by arguing that true happiness cannot be fully attained in this life. While Aristotle saw eudaimonia as achievable through virtuous activity and contemplation, Aquinas posited that human nature, created by God, is oriented toward a supernatural end: the beatific vision, or direct contemplation of God’s essence (Summa Theologica, I-II, Q. 3, A. 8).

Reframing Eudaimonia as Beatitudo

Aquinas’s concept of beatitudo represents a Christian transformation of eudaimonia. He distinguishes between two types of happiness:

- Imperfect Happiness (Felicitas):

- This corresponds closely to Aristotle’s eudaimonia. It is attainable in this life through the practice of virtues and the use of reason. Aquinas acknowledges that humans can experience a measure of happiness through moral and intellectual excellence, as well as goods like friendship and health (Summa Theologica, I-II, Q. 5, A. 5).

- However, Aquinas argues that earthly happiness is limited, as temporal goods—wealth, honor, or even virtue—cannot fully satisfy the human desire for infinite goodness.

- Perfect Happiness (Beatitudo):

- Perfect happiness, for Aquinas, is found only in the afterlife through the beatific vision, where the soul directly beholds God’s essence. This vision fulfills the human intellect’s ultimate longing for truth and the will’s desire for perfect goodness (Summa Theologica, I-II, Q. 3, A. 8).

- Unlike Aristotle’s self-sufficient eudaimonia, beatitudo requires divine grace, as human nature alone cannot attain supernatural union with God.

Aquinas’s distinction reflects his theological anthropology: humans are rational creatures with a natural desire for God, who is the ultimate good. While Aristotle’s eudaimonia is rooted in human potential, Aquinas’s beatitudo transcends it, requiring divine intervention to fulfill humanity’s deepest aspirations.

Virtue and Grace: Bridging Aristotle and Christianity

Aristotle’s ethics emphasize the cultivation of virtues as the path to eudaimonia. Aquinas adopts this framework but expands it to include the theological virtues—faith, hope, and charity—which are infused by God’s grace and orient humans toward their supernatural end (Summa Theologica, II-II, Q. 23–27). While Aristotle’s moral virtues are developed through habit and reason, Aquinas argues that theological virtues are necessary to direct human life toward beatitudo.For example, charity (caritas), the love of God above all, becomes the cornerstone of the virtuous life in Aquinas’s system. It perfects the natural virtues, enabling humans to act in accordance with divine will. This integration ensures that the Aristotelian emphasis on virtue is not discarded but elevated, as natural virtues are ordered toward a higher purpose.

Contemplation: From Theoria to Visio Dei

Aristotle identifies contemplation (theoria) as the highest activity of eudaimonia, as it engages the rational soul in its most divine capacity (Nicomachean Ethics, X.7). Aquinas agrees that contemplation is central to happiness but reinterprets it as the visio Dei (beatific vision). In Summa Contra Gentiles (Book III, Chapters 25–63), Aquinas argues that the ultimate fulfillment of the human intellect lies in knowing God directly, a state achievable only in the afterlife through divine grace.This Christianized contemplation transcends Aristotle’s framework. While Aristotle’s theoria is a human activity directed toward philosophical truths, Aquinas’s visio Dei is a supernatural gift, requiring divine revelation and the elevation of the soul. Thus, Aquinas transforms Aristotle’s intellectual ideal into a theological one, aligning human flourishing with eternal communion with God.

Implications of Aquinas’s Synthesis

Aquinas’s integration of eudaimonia and beatitudo has profound implications for both philosophy and theology. By affirming the value of Aristotelian ethics, Aquinas validates the role of reason and virtue in human life, making his work a bridge between classical philosophy and Christian thought. Simultaneously, his emphasis on beatitudo as the ultimate end underscores the centrality of God in human existence, offering a teleological vision that transcends the limitations of earthly flourishing.This synthesis also addresses a key tension: Aristotle’s eudaimonia is contingent on external goods (e.g., health, wealth, friendship), which can be lost, while Aquinas’s beatitudo is eternal and unassailable, rooted in the immutable nature of God. By grounding happiness in divine union, Aquinas provides a framework that accounts for human suffering and the imperfections of earthly life, offering hope for ultimate fulfillment.ConclusionThomas Aquinas’s synthesis of Aristotelian eudaimonia with Christian theology represents a monumental achievement in intellectual history. By reframing eudaimonia as beatitudo, Aquinas preserves the value of virtue and rational activity while directing them toward a supernatural end: the beatific vision of God. His work in the Summa Theologica, Summa Contra Gentiles, and Commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics demonstrates a profound engagement with Aristotle’s ideas, adapting them to fit a Christian worldview. For Aquinas, true happiness is not merely a human achievement but a divine gift, fulfilling the deepest longings of the human soul. This synthesis continues to resonate, offering a compelling vision of human flourishing that bridges the natural and the divine.

References

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by W.D. Ross. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New York: Benziger Bros., 1947.

Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Contra Gentiles. Translated by Vernon J. Bourke. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1975.

Aquinas, Thomas. Commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by C.I. Litzinger. Notre Dame: Dumb Ox Books, 1993.