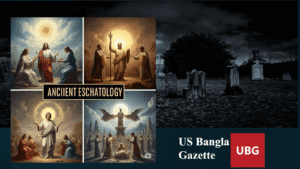

The Origin of the End Times: How Ancient Eschatology Shaped Global Beliefs

The concept of an end time—a period marked by global upheaval, divine judgment, and the renewal or destruction of the world—is a core idea in many religious traditions. The formal term for this is eschatology, from the Greek eschaton (“last”) and logia (“study”), meaning “the study of last things.” Though often associated with Christianity or Islam today, eschatological thought is much older and more widespread, appearing in various forms across ancient cultures.

Zoroastrian Roots: The Birth of Eschatology

One of the earliest and most developed eschatological systems emerged in Zoroastrianism, a religion from ancient Persia (circa 1000 BCE or earlier). Zoroastrian eschatology describes a final confrontation between good and evil, led by a savior figure called the Saoshyant. This culminates in the resurrection of the dead, a fiery purification of the world, and the triumph of good — a vision of cosmic justice and renewal.

This early system introduced foundational themes in eschatology: moral dualism, judgment, resurrection, and the transformation of the world — ideas that would ripple outward into later religious traditions.

Jewish Apocalyptic Thought

As Jewish communities came into contact with Persian culture during the Babylonian Exile (6th century BCE), Zoroastrian eschatological themes began to appear in Jewish writings. The Book of Daniel (circa 165 BCE), with its symbolic visions, resurrection imagery, and prophetic timeline, represents a turning point in Jewish eschatology.

This development marked a shift: instead of viewing history as cyclical, Jewish thought began to adopt a linear view, moving toward a final resolution and divine judgment.

Christianity: A New Frame for the End Times

Early Christianity inherited and transformed Jewish apocalypticism. The Book of Revelation, written around 95 CE, is one of the most iconic pieces of eschatological literature in Western history. It describes the Apocalypse, the rise of the Antichrist, the Second Coming of Christ, the Final Judgment, and the creation of a New Heaven and New Earth.

Christian eschatology became a cornerstone of theology, shaping ideas of salvation, morality, and hope in the face of suffering.

Islamic Eschatology

Islamic tradition also absorbed and reinterpreted earlier eschatological concepts. The Qur’an and Hadith literature contain vivid depictions of the Day of Judgment (Yawm al-Qiyāmah), signs of the end, and the emergence of figures like the Mahdi and Isa (Jesus). These culminate in the ultimate division between the righteous and the damned.

Islamic eschatology emphasizes accountability, divine justice, and the fulfillment of God’s promises — all themes deeply rooted in earlier Abrahamic thought.

Eschatological Echoes Around the World

Outside the Abrahamic religions, eschatological motifs appear in many other cultures:

- Norse mythology speaks of Ragnarök — a series of disasters culminating in the death of the gods and the rebirth of the world.

- Hindu eschatology describes the Kali Yuga, an age of decline that ends with the return of the divine figure Kalki and the restoration of cosmic order.

- Buddhism foretells the coming of Maitreya, a future Buddha who will renew the Dharma.

- Mesoamerican cosmology, particularly that of the Maya, viewed history in cyclical “world ages” that ended with natural and spiritual upheaval.

A Universal Vision of Endings and Beginnings

Although eschatological systems differ in detail, they share common hopes and fears: a desire for justice, a fear of destruction, and a longing for renewal. Whether spoken through prophets, poets, or priests, humanity has long looked to the end, not just with dread, but with the hope that something better might follow.

Today, as we face global uncertainties, eschatology remains a powerful lens through which people interpret history, morality, and destiny.