The Unyielding Soil: Why Max Weber’s “Protestant Ethic” Never Took Root in the Indian Subcontinent

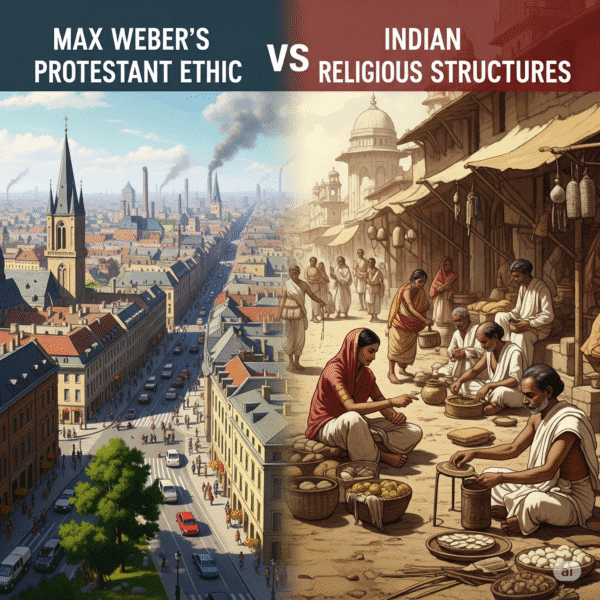

Max Weber’s seminal work, “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism,” posited a profound connection between the ascetic, rationalized worldview of certain Protestant sects and the unique emergence of modern capitalism in the West. His argument highlighted how values such as hard work, frugality, delayed gratification, and the pursuit of a vocational calling, stemming from a quest for signs of divine election, fostered the systematic accumulation and reinvestment of capital. While his thesis has been widely debated and refined, its core insight – that specific religious ethics can shape economic behavior – remains a powerful analytical tool. However, when applied to the Indian subcontinent, Weber’s “Protestant Ethic” thesis conspicuously fails to explain the trajectory of its economic and social development, revealing the deeply entrenched and fundamentally different “civilizational” ethos that resisted absorption.

Weber himself recognized this divergence. In his later comparative studies, particularly “The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism,” he delved into the subcontinent’s religious landscape to understand why a similar “spirit of capitalism” did not spontaneously arise. He concluded that the dominant religious and social structures of India, primarily Hinduism with its intricate caste system and the doctrines of Karma and Dharma, presented a formidable counterpoint to the conditions he identified in Protestant Europe.

The caste system, rigidly stratified and traditionally hereditary, fundamentally constrained social and occupational mobility. One’s birth into a particular caste, determined by past karma, largely dictated one’s occupation, social standing, and ritual purity. This deeply ingrained social structure, reinforced by religious injunctions, discouraged the kind of individualistic, upwardly mobile economic striving central to the “Protestant Ethic.” Why would one relentlessly pursue worldly accumulation and reinvestment if past actions predestined one’s station in life, and one’s duty (dharma) was to fulfill the obligations of one’s current caste, rather than to transcend it through economic means?

Furthermore, the overarching philosophical orientation of Indian religions often emphasized spiritual liberation (moksha) and detachment from worldly desires, rather than active engagement and mastery of the material world as a religious calling. Asceticism in Indian traditions frequently pointed towards renunciation and other-worldly pursuits, contrasting sharply with the “inner-worldly asceticism” of Protestantism, which channeled spiritual discipline into worldly endeavor. The pursuit of wealth, while not necessarily condemned, was rarely imbued with the same spiritual significance as a sign of divine favor or a means of glorifying God. Instead, it was often viewed as a potential hindrance to spiritual progress, fostering attachment and perpetuating the cycle of rebirth.

The British colonial project in India, while imposing its administrative, legal, and educational frameworks, notably failed to instigate a mass conversion to Protestantism. This absence of a widespread religious shift was critical because it meant that the deep philosophical and ethical wellspring of WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants ) civilization remained largely untouched. Native elites, educated in English and conversant with Western legal systems, might have adopted the tools of the colonizers. Still, they did not, for the most part, internalize the core philosophy that made those tools uniquely productive in a capitalist sense. Their inherited cultural and religious frameworks continued to shape their worldview, even as they navigated the complexities of colonial modernity.

While India certainly had forms of trade, banking, and merchant classes – some, like the Jains, even practicing a form of asceticism – Weber argued that these did not coalesce into the unique, rational, and systematic capitalism he observed in the West. The missing ingredient was the ethos – a pervasive, religiously sanctioned motivation for continuous, reinvested accumulation for its own sake, beyond immediate consumption or traditional status.

In conclusion, Max Weber’s “Protestant Ethic” did not, and arguably could not, work in the Indian subcontinent. The profound and enduring nature of indigenous Indian civilizations, particularly their religious and social structures, presented a distinct set of values, motivations, and social organization that fundamentally differed from the European context. The lack of widespread conversion to Protestantism meant that the philosophical core of WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants ) civilization remained unabsorbed, leaving the deep soil of Indian culture largely unyielding to the seeds of Weberian capitalism. The economic and social development of the subcontinent thus followed a path shaped by its own complex historical and cultural forces, a testament to the resilience of “civilization” in the face of colonial imposition.