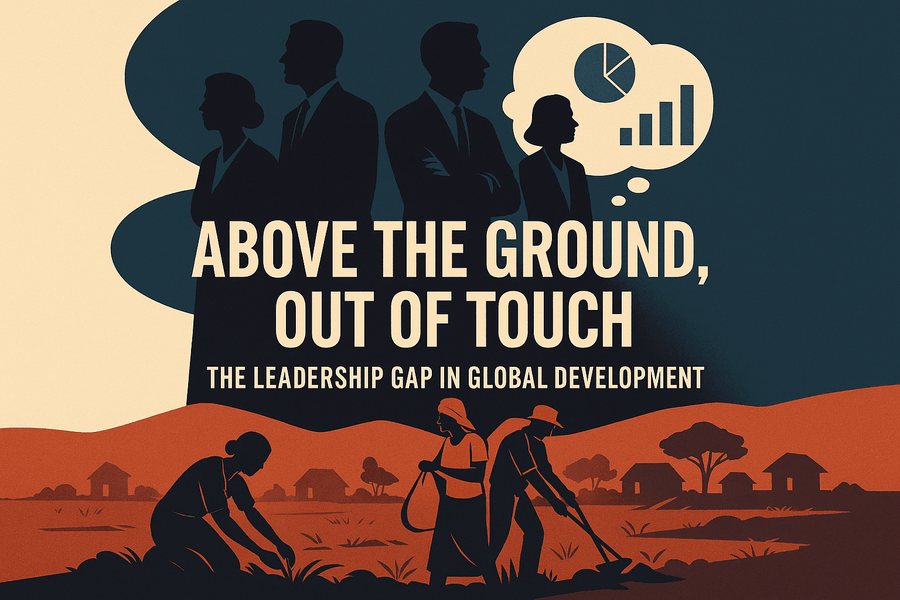

Above the Ground, Out of Touch: The Leadership Gap in Global Development

In ancient Greece, the thinkers who shaped political philosophy were not detached observers. Plato wrote in the shadow of democratic collapse and civil strife, having witnessed the execution of his teacher, Socrates, and having personally advised rulers in Syracuse—sometimes at great personal risk. Aristotle, raised in a family of physicians, educated not only in theory but in the workings of the human body and society, went on to tutor a young Alexander the Great in governance, strategy, medicine, and the practical realities of ruling diverse populations. Their ideas emerged not from abstraction alone, but from proximity to power, conflict, and everyday life.

Today, the scale of influence is vastly larger—but the distance is greater. Senior officials in the United Nations, major non-governmental organizations, and government aid agencies make decisions that shape the lives of billions with far less direct engagement in the conditions those decisions are meant to address. From allocating billions in development assistance to setting priorities for the Sustainable Development Goals, modern development leadership often operates from conference rooms, policy papers, and global summits—far removed from the communities living with the consequences.

This growing separation between authority and lived experience lies at the heart of the leadership gap in global development.

This elite often follows a narrow, privileged pathway: advanced degrees from elite institutions (think Ivy League, Oxbridge, or equivalent), urban/cosmopolitan backgrounds, and careers built on international mobility and high-level networks. Socioeconomic diversity remains limited—persistent barriers block those from less privileged origins from accessing top roles in education, professions, and policy. High educational attainment correlates with middle-to-upper-class origins that enable such paths, creating a self-reinforcing cycle far removed from survival-level realities in the Global South or even domestic working-class contexts.

Compounding this is a personal dimension: many in these circles come from disrupted family backgrounds themselves. While granular data on family histories of specific UN/NGO/government aid officials is scarce due to privacy, broader patterns in international civil service and elite professions show elevated rates of family strain. The demands of frequent postings, long hours, and work stress contribute to high divorce rates among UN couples (anecdotal reports from staff forums suggest figures as high as 90%+ in some contexts, though unverified officially). UN policies even include provisions like single-parent allowances, recognizing non-traditional family structures as common. In elite cohorts more generally, delayed marriage, higher dissolution, and single-parent challenges arise from career pressures—mirroring trends in higher-income, educated groups.

These factors narrow experiential models further. Without deep immersion in multi-generational households, traditional community resilience, or the everyday “refusals-to-try” rooted in dignity, habit, or fear of incompetence, policy perspectives can remain theoretical. Decision-makers may prioritize abstract frameworks—top-down targets, capacity-building models, or tech-forcing initiatives—over the motivation gaps, cultural barriers, or protective identity choices observed in real populations. The result: projects that falter because they overlook why people resist change, not due to “lack of capacity” but to preserve autonomy and self-respect.

This detachment sustains a form of hegemony. Critiques of the “ivory tower” in development and international relations highlight how insulated institutions reproduce dominant narratives—framing grounded frustrations as mere stereotypes or myths while claiming evidence-based neutrality. Policies shaped in Geneva, New York, or Brussels bubbles often ignore on-the-ground family dynamics, cultural norms, or practical incentives, leading to inefficiencies, wasted resources, and unintended inequities.

The ancients understood that true wisdom requires bridging theory and practice. Plato’s failed Syracuse experiment and Aristotle’s tutoring of Alexander were “real-world” tests—immersion in survival-level politics, military strategy, and human behavior. Modern elites lack an equivalent: no prolonged entanglement in the gritty contexts their decisions reshape. Philosophy—or policy theory—stays more conceptual, less rigorously tested against lived realities.

This gap has serious consequences. When refusal patterns (to tech, new livelihoods, or change) scale to power positions, they create bottlenecks, stress subordinates, and drag on innovation. In development, it means aid that misses the mark, perpetuating cycles of dependency rather than empowerment.

Bridging this divide demands structural change: greater representation of locals with diverse family and economic realities in decision roles, mandatory field immersion for policymakers, and humility in acknowledging that elite paths can blind one to the dignity-driven choices of billions. Until then, the contrast remains: Plato and Aristotle wrote for princes while rooted in the world they sought to improve. Today’s development elites shape the lives of billions—yet too often from an ivory tower that feels worlds away.