From Soviet Muse to NGO Advocate: The Postcolonial Pivot of Third World Poets

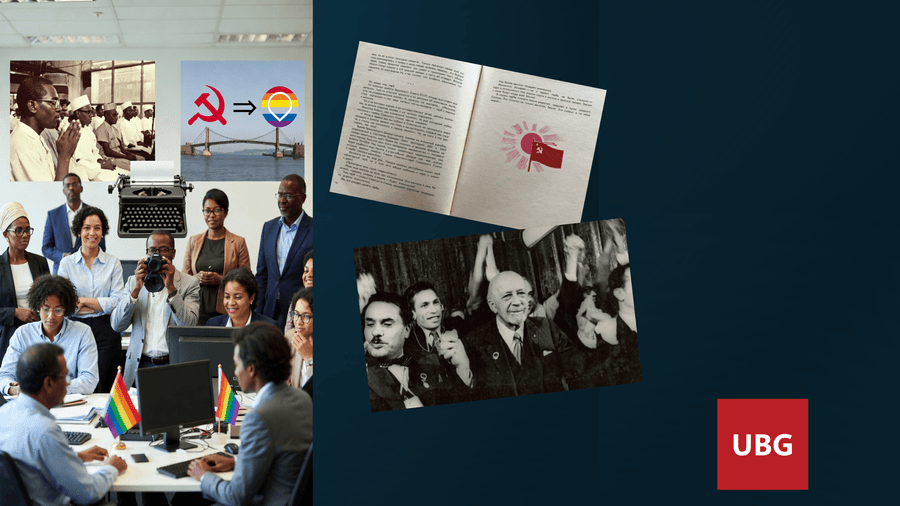

In the turbulent decades following World War II, poetry emerged as a potent tool of resistance and imagination in the decolonizing world, often referred to as the “Third World” during the Cold War era. Marxist-leaning intellectuals and artists, drawing on a rich tradition of revolutionary verse from figures like Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong, found in poetry a means to articulate anti-imperialist sentiments, class struggles, and visions of collective liberation. This affinity was not organic alone; it was actively cultivated through Soviet cultural diplomacy, which invested heavily in Third World poets to foster alliances against Western hegemony. However, with the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, many of these poets and their networks underwent a profound transformation, morphing into participants in the “NGO-ization” of activism—a process where radical movements professionalized under Western-funded nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), often shifting from revolutionary fervor to reformist advocacy.This twist reveals the enduring interplay of geopolitics, culture, and power in shaping postcolonial literary landscapes.

The centerpiece of this effort was the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association (AAWA), launched in 1958 at the Tashkent conference, followed by a series of congresses across the socialist world and allied capitals. The USSR funded the multilingual Lotus magazine (1968–1991), which published poetry, prose, and criticism from African, Asian, and later Latin American writers, creating a shared anti-imperialist literary canon. The Lotus Prize, often described as the Afro-Asian equivalent of the Nobel, brought prestige and cash. Scholarships to Moscow’s Gorky Literary Institute, sponsored tours to the Soviet Union and its satellite countries, stipends, residencies, and publishing opportunities provided material support in often economically fragile postcolonial contexts.

For many poets in the 1970s and 1980s, it was difficult to remain untouched by these networks. The emotional and communal power of poetry—precisely what Plato had feared two millennia earlier—was harnessed to advance socialist internationalism and revolutionary sentiment. The result was a visible saturation of Soviet-sympathizing or leftist-leaning voices in Third World literary scenes.Then came 1991.

The collapse of the Soviet Union severed the funding overnight. Lotus ceased publication. The AAWA faded into inactivity. Stipends, scholarships, tours, and prizes disappeared. Many poets and intellectuals, already accustomed to institutional patronage for their livelihood and visibility, faced a stark choice in neoliberalizing postcolonial economies where public arts support had dwindled and structural adjustment programs tightened budgets.

They adapted. A significant number transitioned into the growing ecosystem of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), which by the 1990s were expanding rapidly under Western liberal and donor funding. Human rights, freedom of expression, cultural rights, gender equality, and civil society development became the new thematic terrain. The same anti-oppression rhetoric persisted—now reframed in terms of individual rights, good governance, and democratic reform rather than class struggle or socialist revolution. The professionalization of activism, often called “NGO-ization,” turned radical energies into salaried projects, grant applications, workshops, reports, and international conferences.

The pivot did not end there. By the 2010s and 2020s, many of these networks and individuals had moved further into the corporate-aligned domains of ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) investing and LGBTQ+/DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) advocacy. The “Social” pillar of ESG, corporate diversity programs, impact funds, and foundations supporting inclusive development in the Global South created new funding streams and professional opportunities. Former revolutionary poets or their intellectual heirs became consultants, trainers, policy advisors, and project leaders in areas such as workplace inclusion, gender and sexual diversity, anti-discrimination campaigns, and “social impact” reporting.

The underlying dynamic remained strikingly consistent: external powers continued to cultivate and steer Third World intellectuals and cultural producers to serve broader geopolitical and economic agendas. Only the patron changed—from Moscow to Western liberal institutions and multinational corporations—and the language shifted from socialist solidarity to inclusive capitalism.

This arc—from Soviet-backed revolutionary verse to NGO professionalism to ESG/LGBTQ+ business—illustrates how poetry’s mobilizing power, once feared by Plato for its ability to stir passions and shape souls, has repeatedly been channeled by whoever controls the platforms, purses, and prevailing ideological frameworks. For those who knew many of these poets personally across four decades and multiple continents, the story is not merely historical; it is deeply human—a chronicle of idealism, adaptation, survival, and the persistent pull of external influence on the postcolonial imagination.